On July 7, 2025, a Texas Army National Guard UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter struck a Texas Department of Public Safety drone during flood-response operations along the Guadalupe River near Kerrville. The helicopter landed safely. Early speculation in the community and on social media focused on the idea of a rogue civilian drone operator flying recklessly during an emergency. Some of DJI's biggest critics and U.S. Drone manufacturers ran with the narrative. The 241 page investigative incident report obtained by The Zero Lux after a final Attorney General ruling, confirmed that the drone belonged to Texas DPS, was flying an authorized mission, lost GPS and command link shortly after launch, and was no longer within visual line of sight when the collision occurred.

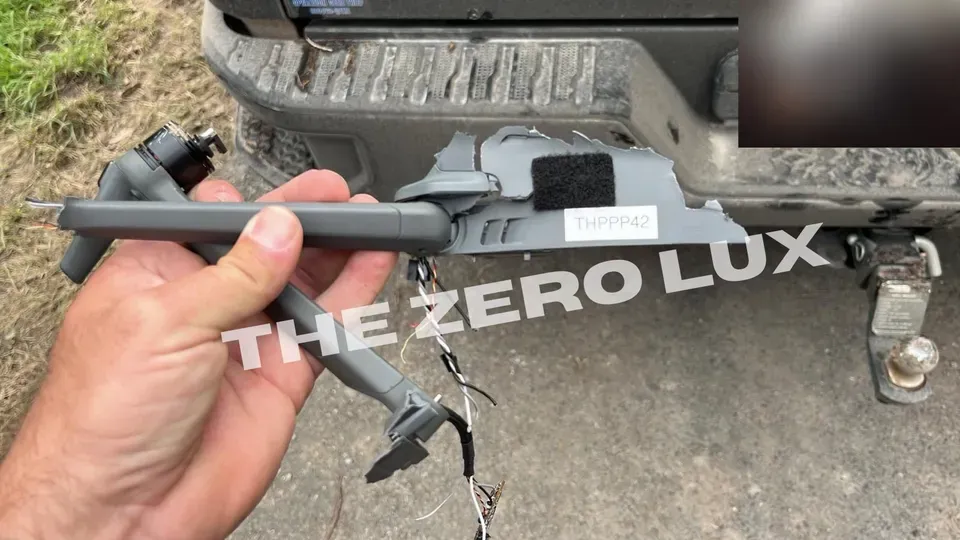

According to DroneSense telemetry included in the report, Trooper Kendall Gray launched a DJI Mavic 3T labeled THPPP42 at approximately 3:56 p.m. from a roadside area on Lazy Creek Road. The drone climbed to roughly 211 feet, consistent with a 200-foot operational altitude used for flood-mapping assignments. The DroneSense record shows the aircraft began moving east along the river, but within about two minutes of launch it lost GPS, then lost its control link. DroneSense telemetry shows the aircraft traveled roughly half a mile downriver from the launch point before the collision, a distance that could not have been maintained under visual line of sight. At that distance, the drone would not have been visible to an operator standing at the launch point, especially at low altitude along a tree lined river. Gray attempted to activate return to home (RTH), but the connection was not restored. In a recorded interview summarized by Texas Ranger Alan Rackley, Gray acknowledged that he did not maintain visual line of sight as the drone continued downriver after the signal loss.

At roughly the same time, an Army National Guard UH-60 crewed by CW2 Carmichael was flying westbound along the same river corridor at approximately 250 feet. According to the Ranger’s summary, the helicopter crew reported that the Joint Air Ground Coordination Team (JAGCT) had told them drones operating in the area would be flying at or below 150 feet. This altitude guidance was incorrect. DPS drones in the region were operating around 200 feet, and the DroneSense data shows the Mavic 3T at about 211 feet shortly before impact. The Ranger report also documents that the helicopter crew announced their position on CTAF 123.025 as they flew the river.

The DPS drone team told investigators that they were monitoring radio traffic but heard no helicopter calls. The packet clarifies what happened: Gray was listening to 122.7, while his partner, Trooper Bustamante, monitored 123.025. The helicopter broadcast on 123.025. This frequency split meant the pilot in command of the drone was not listening to the same air-to-air channel as the helicopter crew. The Ranger report does not assign intent or fault regarding frequency selection, but the sequence is clear: the aircraft were on different channels, and no one heard the other’s transmissions.

The helicopter crew reported seeing the drone at approximately eye level and initiated a descent to avoid it. During that maneuver, the drone struck the helicopter’s tail rotor, damaging two blades. The UH-60 made a precautionary landing in a nearby clearing. Maintenance personnel inspected and rebalanced the rotor before the crew flew the aircraft back to Kerrville Airport. Ranger Rackley documented the debris field, photographed the recovered pieces, and collected evidence including the drone’s arm, motor, and cabling. His findings matched the DroneSense logs: the drone did not stall, did not rapidly climb above its assignment, and was on its programmed flood-survey path when it lost GPS and link.

The internal DPS report includes an early summary that mistakenly listed the drone as a Mavic 2, reflecting confusion in the immediate aftermath. Later records, photographs, and the physical debris all confirm the aircraft was a Mavic 3T. Internal communication also shows that Gray did not know at the time of the flight that his aircraft had struck the helicopter; he learned about the mid-air collision from a DPS UAS group chat. The Human Factors section of DPS’s risk assessment lists “PoorCommunication” as a contributing element in the incident.

DPS grounded all drone operations in the region the following day. A multi-agency directive was later issued formalizing deconfliction procedures, including altitude separation rules and explicit requirements for radio coordination between UAS operators and crewed aircraft. The directive also established a new protocol requiring pilots to announce “UAS flyaway, UAS flyaway, UAS flyaway” on airband frequencies in the event of link loss. The investigative packet shows this call was not made on July 7, and no alert was broadcast on the Joint Air Ground Coordination Team channel during the loss of GPS and link.

In the days following the collision, DPS Aviation personnel documented the drone’s maintenance history and submitted the information to the FAA. Inspector Garry Mitcham noted that DPS maintained a thorough and active maintenance program, and no mechanical issues were identified with the drone prior to the flight. FAA Safety Team Manager Ryan Newman wrote in an email to DPS that the collision fit into a pattern of helicopter-UAS conflicts nationally and would likely be recorded as “helicopter/UAS collision number 18” in the FAA’s internal safety case files. In the same correspondence, FAA Supervisor Emma Morales stated that the agency did not intend to initiate any administrative or enforcement action and would use the information for safety outreach and training.

Public understanding of the event developed differently. Because no technical details were released immediately, early assumptions filled the void. When The Zero Lux first contacted the City of Kerrville for clarification on July 22, the city said it had no information and that DPS held the investigation. On July 23, during a legislative hearing on the Hill Country floods, state officials briefly stated the drone was authorized but also commented that it had “flown too high and stalled.” That phrasing does not appear in any of the DPS, FAA, or NTSB records. Multirotor drones do not stall in the aerodynamic sense, and the investigative materials contain no reference to altitude deviation or stall behavior.

On July 30, the City of Kerrville posted a clarification acknowledging that the drone involved in the collision was an authorized DPS aircraft. The same post repeated the “flew too high and stalled” language. Comments were disabled. When contacted the following day, the city’s public information officer said he had first learned of the corrected information by reading a news article and had not received the technical findings from DPS. The 241 page incident report released months later contains no evidence supporting either claim from the city’s statement.

During the July 15 congressional hearing and the July 23 state legislative hearing, industry representatives cited the Kerrville collision as an example of the risks posed by unauthorized civilian drones. Both DroneUp and AUVSI later acknowledged their testimony was based on incorrect early information, but neither organization has issued a public correction or clarified the record in the forums where their initial statements were made. The investigative records do not support any of the claims made during those hearings.

The investigative incident report provided to The Zero Lux were released only after the Texas Attorney General issued ruling OR2025-037720 on October 20 and instructed DPS on which materials must be disclosed. The report includes DroneSense logs, evidence-collection forms, photographs, internal emails, Ranger summaries, FAA and NTSB correspondence, and the post incident deconfliction directive. All technical information matches the flight data and debris photographed on July 7.

The sequence described across DPS, FAA, NTSB, and Ranger documentation is consistent. The drone was launched for an assigned mission, lost GPS shortly after launch, lost command link, continued downriver beyond visual line of sight, and entered the flight path of a National Guard helicopter operating at a nearby altitude. The helicopter crew relied on altitude guidance from JAGCT that did not match the altitudes DPS drones were actually using. The drone pilot in command monitored a different radio frequency than the helicopter. The two aircraft did not hear each other. The helicopter descended to avoid the drone, and the drone struck the tail rotor.

The early public narrative did not match the technical record. The incident report shows no evidence of a rogue civilian drone, no evidence of a stall, and no evidence that the aircraft exceeded its assigned altitude in any meaningful way. The cause rests with signal loss, a lack of visual line of sight, misaligned radio monitoring, and mismatched altitude expectations during concurrent emergency operations.

The FAA described the Kerrville collision as a learning case, writing that the goal was understanding and to see what lessons can be learned, and noting that it was ‘NOT an enforcement investigation.’

Raising a question: would the FAA have responded the same way if the aircraft had actually been a rogue civilian drone, as was falsely reported? In recent years, the FAA has issued substantial penalties in cases where civilian drone pilots endangered crewed aircraft, including fines for near misses with helicopters and certificate suspensions for flying beyond visual line of sight or entering restricted airspace. In the Kerrville case, FAA correspondence shows the agency classified the event as a safety case, not an enforcement investigation, and focused on what lessons could be learned from the incident.

The Zero Lux will be releasing the full incident report when we finish retracting sensitive materials. Tensions are high, there are non-public phone numbers and emails to law enforcement and aviation experts in this report.