They’re not hiding. They’re governing. That’s how one U.S. counterterrorism official described Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen (JNIM), the West African al-Qaeda affiliate that has quietly built one of the most adaptable, well-resourced, and locally embedded jihadist insurgencies in the world. While international media fixates on Gaza, Ukraine, and Latin America, a silent revolution is unfolding across the Sahel—a war of influence, taxation, propaganda, and yes, drones.

The rise of JNIM in West Africa: recruitment, governance, and military evolution all visible to those willing to look. The group’s propaganda outlet, Az-Zallaqa Media Foundation, never stopped transmitting. Despite geo-blocking and Western platform takedowns, their battlefield updates, martyrdom eulogies, and drone footage continued to circulate across X, Telegram, dark web forums, and invite-only sites.

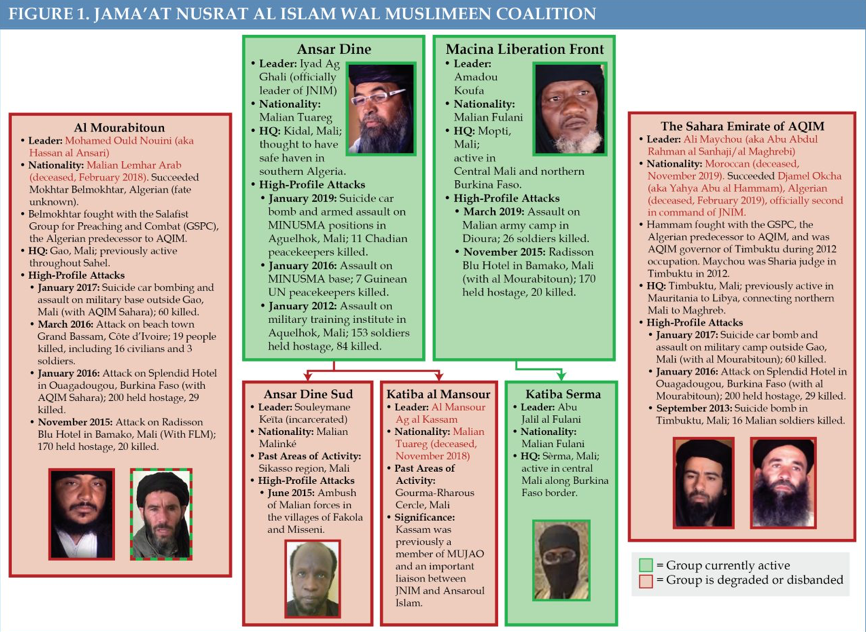

JNIM’s origin story began not just with guns, but with grievance. In Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, the group capitalized on deep local resentments—corrupt governments, abusive militaries, ethnic fractures. Their messaging, much like the Taliban or HTS in Syria, promised protection, justice, and the restoration of dignity. And for many communities abandoned by their own governments, they delivered. “JNIM is attempting to portray itself as a legitimate governance structure,” said Dr. Levi West in an interview with The Cipher Brief. “In a way that mirrors what we saw with the Taliban or HTS.”

By 2023, JNIM was no longer just a terrorist group. It had become an insurgency. In some towns, it operated courts. In others, it taxed agricultural production. And in many cases, its fighters were more familiar—and more trusted—than the distant state.

But behind the governance was blood. Images showed the aftermath of summary executions—bodies lined in ditches, some bound, others burned. Civilians accused of spying. Men targeted for refusing allegiance. In one sequence, a child’s lifeless body lay crumpled near a village well, caught in the crossfire of a so-called liberation. These weren't isolated incidents; they were framed, documented, and distributed through Az-Zallaqa as proof of control.

The media wing didn’t just glorify martyrdom or battlefield success—it memorialized terror. Fighters posed with weapons, circled captured towns, and filmed the wreckage of ambushed convoys. In one clip, a man identified as a local farmer was shot execution-style after a “trial” before masked jihadists. Another showed children marching through a village square, raising the black flag above a government school.

To those tracking the feed, the message was clear: this was not just about insurgency—it was about erasure and replacement. State by state, checkpoint by checkpoint, flag by flag.

AFRICOM Commander Gen. Michael Langley warned, “We’re seeing an arc of instability stretch across the Sahel. In some places, these groups have more influence than state governments.”

Weapons arrived not through one pipeline but many. According to multiple sources and field reports, JNIM fighters acquired arms through black market channels, looting military bases, regional smuggling, and corruption at border crossings. Experts from the Policy Center for the New South noted a persistent flow of weapons from Libya, Nigeria, and gold mining corridors. These included Kalashnikovs, anti-tank rockets, loitering munitions, and increasingly—commercial drones modified for attack.

The drone evolution came slowly, then all at once. At first, JNIM deployed commercial drones purely for reconnaissance: spotting Burkinabe and Malian patrols, surveying base layouts. But as early as 2023, battlefield imagery began to show crude modifications. Aerial grenades. Plastic bottles repurposed as drop devices. A series of failed attacks drew little attention outside the region. But internally, they were treated as prototypes. A learning curve.

JNIM-operated drones show a clear shift toward modular, non-OEM construction. One unit features a modified arm lacking any manufacturer branding, with mismatched screws and black housing not found on commercial models. Another displays a drop bracket secured with red cloth — a technique seen in homemade grenade delivery attempts. Several components appear to be sourced from commercial marketplaces like Alibaba and AliExpress, where unbranded drone parts, imitation Autel-style arms, and payload accessories are readily available. While some configurations may still rely on DJI-style airframes, others show signs of hybrid assembly and low-cost cloning — a practical adaptation to sanctions, surveillance, and battlefield losses.

Some of the drones bore no visible branding. No DJI or Autel markings. No RTK modules. Their arms were blank — likely cloned in Shenzhen or sourced from the global grey market. And yet, they flew. One video circulating in jihadist channels appears to show a drone deploying a munition with precision onto a Burkinabe military checkpoint. The moment was captured from both the air and the ground — a sign of confidence not just in outcome, but in propaganda value.

“The most dangerous thing about JNIM is that they’re patient,” said a regional counterinsurgency advisor. “They’re not wasting resources. They test. They iterate. They adapt. And they’ve got nothing but time.” A tactical assessment published by Grey Dynamics in 2025 echoed that view: JNIM isn’t trying to win overnight. It’s trying to outlast and out-govern.

The financing for this insurgency? Increasingly international. According to a July report from the Atlantic Council, drug trafficking routes across the Sahel have become a core funding source for militant actors. Cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin move through West Africa en route to Europe—and some shipments reportedly originate in Latin America. That alone raises a troubling possibility: JNIM may be in quiet contact with Latin American cartels or Hezbollah facilitators. “There’s no other way for that kind of logistical coordination to function,” said one former DEA field agent familiar with West African trafficking corridors. “Those are handshake deals. There’s intent behind them.”

And the fighters? They’re not just local. While JNIM’s ranks are heavily Tuareg and Fulani, intelligence assessments suggest that training camps have drawn foreign nationals—from Mauritania, Libya, and even the Middle East. Captured smartphones in the Mopti region have revealed Arabic-language material from external trainers. Others show GPS coordinates tied to desert locations near the Mali-Algeria border, long known to host jihadist safe havens and weapons caches.

Propaganda, meanwhile, never stopped. Despite Western efforts to block and remove Az-Zallaqa Media, JNIM's media wing has evolved. They’ve embraced redundancy: backups on Russian servers, videos encoded to bypass upload filters, and ZIP archives passed hand-to-hand or via burner Telegram channels. The message is simple: “We are here. We are growing. We are inevitable.”

One U.S. intelligence briefing from early 2025 even flagged the possibility that some JNIM propaganda was being translated for external distribution. English subtitles. French voiceovers. The group is not just fighting—it’s recruiting. And it knows the West is watching.

The most recent ACLED data shows a dramatic uptick in JNIM-claimed operations in the second quarter of 2025. Attacks on military outposts in northern Burkina Faso have increased in both frequency and lethality. Drone-assisted strikes are now reported in three distinct regions, with verified images showing explosive payloads and target area destruction.

In some cases, the group has even outmaneuvered Russian paramilitary units. The shadowy Africa Corps, a successor to Wagner Group, has faced repeated ambushes and IED attacks in areas where JNIM enjoys terrain dominance and local support. A recent Le Monde report noted: “Despite Russian air support and armored columns, the jihadists remain mobile, informed, and deeply embedded.”

The international community’s silence on this front is deafening. As the world focuses elsewhere, the Sahel edges closer to full-blown state failure in multiple zones.

“What distinguishes JNIM is its hybrid nature—an al-Qaeda-aligned movement that embeds within local grievances and tribal fault lines,” Cipher Brief analysts wrote. “It isn’t just a jihadist insurgency. It’s a parallel order.”