On a hot August day, a wildfire climbs the canyons of the western U.S. Smoke columns rise like storm fronts. Above them, helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft crisscross in a tight, low-altitude ballet—dropping water, mapping heat, or guiding tanker drops through narrow airspace. Then, a drone appears. To the person flying it, it might be just a drone. But to the pilots in the air, it’s a threat. Firefighting aircraft don’t have the luxury of guessing what type. If they see a drone, they pull out.

“People think they have the right to fly drones wherever they want, but it’s a privilege, not a right,” says Kyle Nordfors, often tasked to remote terrain where wildfire and public safety missions converge.

“There’s a difference between having the ability to fly and the authority to fly,” Nordfors explains. “Wildfires are one place where that distinction becomes life-or-death.”

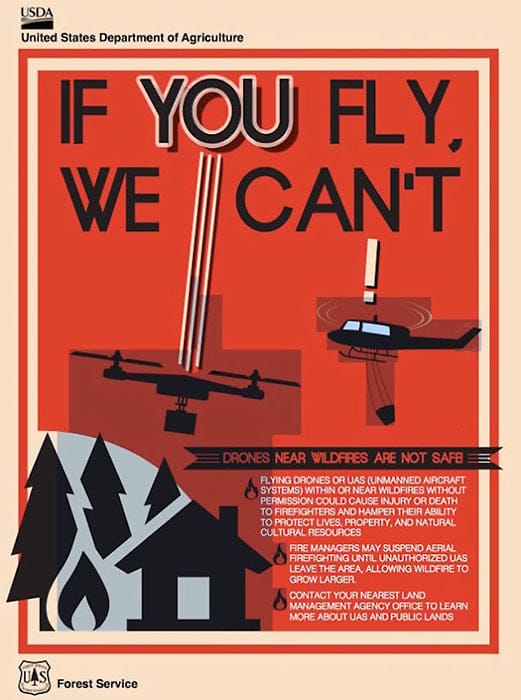

This warning sign, displayed by fire agencies across the country, underscores a simple rule that’s echoed coast to coast: If You Fly, We Can’t.

Drone incursions around active wildfires are on the rise, according to data compiled by the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). As of August 2025, NIFC has documented 28 drone incursions, nearly double the number reported by this time last year. California alone accounts for 21 of those incidents. Dozens of incursions are reported annually, and just one can ground air operations across the entire fire zone.

“People don’t realize the chain reaction one drone can trigger,” Nordfors says. “You force a plane to pull back, you lose eyes on the fire. That affects evac zones, firefighter safety, even whether a hotshot crew can safely advance. And it all traces back to a drone someone wanted to fly for fun.”

Firefighting aircraft—leadplanes, air tankers, helicopters, and paracargo jumpers—routinely fly as low as 150 to 200 feet above ground during wildfire suppression. That’s the same airspace where many consumer drones operate. The FAA allows hobbyist drones to fly up to 400 feet in uncontrolled airspace, meaning this critical overlap creates a recipe for disaster. Most drones lack advanced sense-and-avoid systems and rely on forward-facing cameras, leaving vast blind spots in the sky. Even well-meaning drone pilots can unknowingly drift into a manned flight path. And when that happens, firefighting aircraft are forced to abort—grounded immediately for safety—disrupting air drops, delaying suppression, and putting crews on the ground at greater risk.

And it’s not just collisions. Helicopters are particularly vulnerable. The rotor wash of a hovering helicopter creates a suction dynamic that can literally pull a small drone into the blades. Federal law does exist to address these intrusions. On Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land, flying a drone that interferes with a wildfire response violates 43 CFR 9212.1(f). In Idaho, the penalty includes a $500 fine and a mandatory court appearance—though fines vary by state.

In one of the most high-profile incidents, Peter Tripp Akemann of Culver City pled guilty to recklessly operating a drone into the path of a Canadair CL‑415 “Super Scooper” water bomber battling the Palisades Fire in Los Angeles. The collision punched a 3‑by‑6‑inch hole in the aircraft’s wing, grounding it for days at a critical moment in the blaze. Akemann has agreed to pay over $65,000 in restitution, complete 150 hours of wildfire-related community service, and faces up to one year in federal prison for the misdemeanor charge. Federal prosecutors emphasized that—despite any claim of curiosity—his actions endangered first responders and compromised a vital firefighting asset.

A Super Scooper firefighting aircraft was hit by a drone while battling the Palisades Fire in Los Angeles. The collision, which occurred on January 9, 2025, resulted in a 3x6 inch hole in the plane's wing and caused it to be grounded for several days.

But enforcement is hard. By the time air crews detect a drone and operations are grounded, the pilot may already be gone. Even when caught, citations often hinge on whether the incursion is deemed “egregious” enough for mandatory judicial review.

“The problem is deterrence,” Nordfors says. “Until there are real consequences, people think it’s just a warning. They don’t grasp that firefighters may have had to stop protecting homes because of that drone.”

From the ground, the disruption isn’t just tactical—it’s personal.

“When you lose aerial support during an op, everything slows,” Nordfors says. “There are times we’ve had to pull back completely. That puts structures at risk. It puts crews at risk.”

Photos from recent wildfires show what happens next: exhausted hotshot teams retreating while fire lines breach containment. Helitack crews grounded. Coordination lapses. In some incidents, evacuations are delayed because a fire’s behavior couldn’t be monitored from above in real time.

Firefighters fighting Utah fires

“This isn’t about gatekeeping airspace,” Nordfors insists. “But when we’re flying a helicopter with eyes on the perimeter or trying to drop retardant between a canyon wall and an evacuation corridor, there’s no margin for error.”

The official stance is clear. As stated in the NIFC’s official guidance:

“Regardless of your motivation, flying a drone near a wildfire is putting someone else’s life in danger. Your hobby is not worth another person’s life.”

— National Interagency Fire Center

Their materials go further, urging government agencies, media, and hobbyist organizations to actively educate the public. Programs like Know Before You Fly exist, but Nordfors thinks we need more than public education. It’s not just about enforcement mechanisms. We need to flip with safety—to value the choice to stay grounded over getting the shot. That’s how we build a safety culture.

Despite advances in drone accessibility, Nordfors believes the industry has neglected a critical pillar: education. “Nobody’s teaching people this stuff,” he says, emphasizing that many drone users have no concept of the hazards they introduce near active wildfires. The platforms don’t warn about airspace restrictions, influencers rarely mention fire zones, and manufacturers too often treat flight as a right, not a responsibility. His concerns mirror those of other aviation safety experts. In 2021, the FAA’s own UAS Safety Team stressed the need for "risk-based education" and proactive public awareness to prevent midair conflicts. Organizations like DroneResponders have also called for stronger integration of airspace safety briefings into consumer platforms and flight apps. For Nordfors, it’s not just about penalties—it’s about making sure drone operators understand that when they fly near wildfires, they’re not just breaking the rules. They’re putting lives at risk.

In an era where every perspective is a drone flight away, the stakes near wildfires aren’t cinematic—they’re life and death. Until policy, platforms, and public awareness catch up, the burden will keep falling on pilots like Nordfors to pull back, stand down, and hope the fire doesn’t gain ground while they wait.