On the afternoon of August 20, 2025, at the Eagle Pass–Piedras Negras bridge, U.S. authorities revoked the tourist visas of Sonia Villarreal Pérez and her husband, Jorge Miguel Barajas Hernández. Villarreal, who serves as Subsecretary of Government for Coahuila’s northern region and is a former mayor of Piedras Negras, told Proceso she believed the action was due to her pregnancy. “I suppose it’s because of my pregnancy,” she said, explaining she had planned to cross to Texas for a gynecological visit. But visa cancellations in the United States do not work like parking tickets. They are rarely closed cases. More often, they are the mark of an ongoing investigation.

BREAKING: Another Mexican official gets visa revoked.

— Auden B. Cabello (@CabelloAuden) August 23, 2025

Sonia Villarreal Pérez, the current Subsecretary of Government for the Northern Region of Coahuila and former mayor of Piedras Negras, had her U.S. tourist visa revoked (along with that of her husband, Jorge Miguel Barajas… pic.twitter.com/2VhO8224ES

It is true that under current U.S. policy, including President Trump’s January 2025 order against “birth tourism,” women arriving late in pregnancy may be scrutinized or denied entry. Villarreal’s account is not impossible. But her explanation skirts the fact that she was not traveling alone. Her husband, Jorge Miguel Barajas Hernández, was once known by another name: “El Hummer.” His career in law enforcement, stretching back to the Grupo de Armas y Tácticas Especiales (GATE), has been haunted for more than a decade by allegations of terrorism, cartel collusion, and human rights abuses.

The record begins in 2012, when two car bombs detonated in Nuevo Laredo, one outside the Public Security building in April, another at City Hall that June, killing one and injuring six. The following year, the Fourth District Court of Coahuila issued arrest warrants in criminal process 78/2013-IV, naming Barajas, then a GATE officer, along with Héctor Flores Rodríguez, alias “El Jaguar.” Federal prosecutors alleged that the bombs had been prepared by GATE and escorted by its members to the Tamaulipas border, where cartel operatives detonated them remotely. Two men arrested in connection with the attacks, Carlos Fernando Araujo Garza and Roberto Sánchez Anaya, testified before the Federal Public Ministry that they belonged to a Gulf Cartel cell under Rolando “El Rolys” Velázquez Caballero. In their sworn declarations, they described meeting with GATE commanders in Saltillo and stated: “It was GATE officers who prepared the cars with explosives,” naming Flores and Barajas. They further testified that the bombs were then escorted across Coahuila “so that no one would interfere” before being delivered into Nuevo Laredo, where they were detonated remotely. Those statements became the basis for the terrorism charges.

Almost none of that remains visible in the public record. The articles that once put “El Hummer” alongside the car bombs of 2012 have slipped out of sight, surviving only in forum reposts, PDF captures, and archived versions of newspapers that were later threatened into silence. For most readers, the story has been erased in practice, if not in fact.

The coverage did not disappear by accident. Local outlets that pursued the car-bomb angle became targets themselves. El Mañana de Nuevo Laredo, which had reported aggressively on organized crime and state complicity, was attacked repeatedly—shot at, bombed, hacked—and by 2012 publicly announced it would stop covering drug violence after its newsroom was riddled with bullets. What survives of its reporting on the car bombs and the police escorts exists now only in the archives.

And yet, Barajas’ career continued without interruption. By 2015 and 2016, regional papers were still referring to his name in connection with those warrants, even as he appeared at ceremonies during the unveiling of Fuerza Coahuila, the new police brand meant to replace the discredited GATE. A column in El Demócrata put it in blunt terms: “the same mattress, with new sheets.”

In photographs from the 2016 Fuerza Coahuila launch, Barajas sits in the front row as a “guest of honor,” shoulder to shoulder with the inner circle of Government Secretary Víctor Zamora and loyalists of Armando Luna Canales. The image underscored what human-rights observers argued at the time — that the rebranding exercise was superficial, recycling the same operators who had already been accused of abuses under GATES.

2016 Fuerza Coahuila launch event. Jorge Miguel Barajas Hernández (“El Hummer”) sits in the front row as a guest of honor, alongside figures aligned with Government Secretary Víctor Zamora and collaborators of Armando Luna Canales. The image illustrates how GATES commanders were retained under the new Fuerza Coahuila banner.

In 2018, narcomantas appeared in Piedras Negras, accusing a local commander of being “protected by Miguel Hernández Barajas ‘El Hummer.’” The banners claimed protection networks, extortion rackets, and trafficking. They were anonymous allegations, not judicial findings, but they extended the shadow that had hung over his name since the bombs.

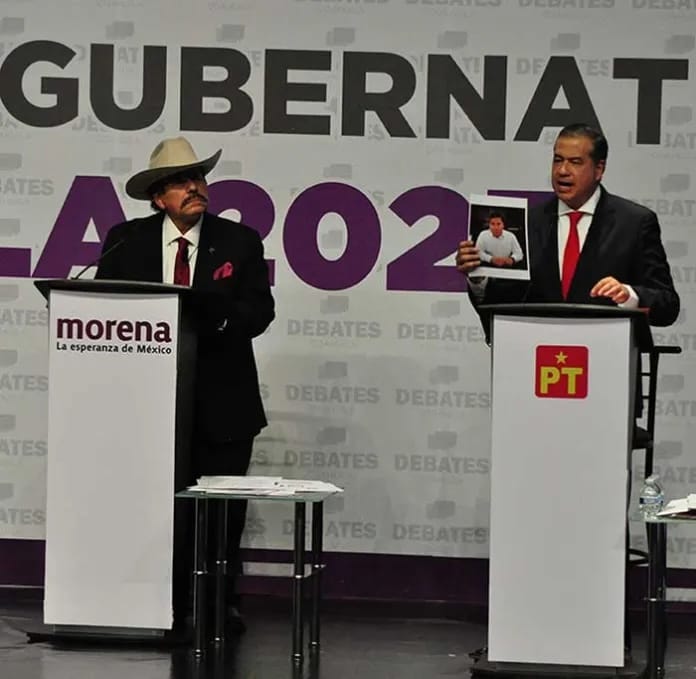

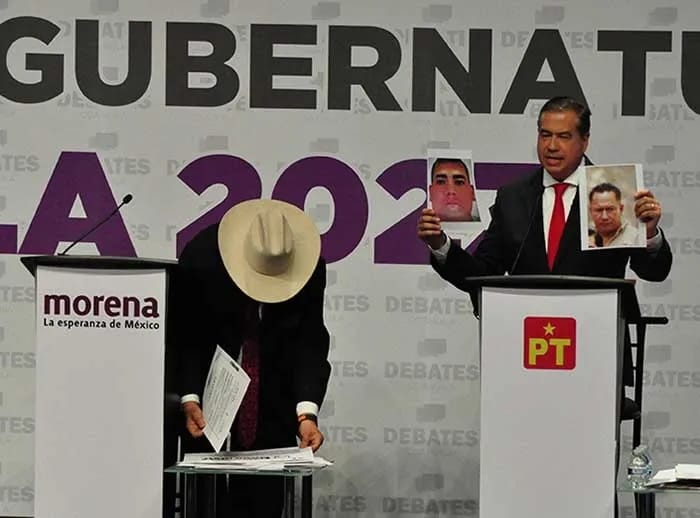

Barajas's past resurfaced in politics in 2023. At a gubernatorial debate in Coahuila, candidate Ricardo Mejía Berdeja stood on stage and held up Barajas’ photo, alongside Héctor Flores “El Jaguar” and another commander known as “El Bóxer.” Mejía accused them of being behind the state’s crystal meth trade and of carrying out years of human rights abuses under the Fuerza Coahuila banner. “They are the unspeakable ones,” Mejía told the audience, lifting the photos high so the cameras could capture them. “Behind them are the crystal sales, the invasions, the abuse of our young people.” For viewers watching at home, the message was unmistakable: these weren’t ghosts from the archives, but names and faces still central to Coahuila’s present.

Coahuila gubernatorial debate 2021. Candidate Ricardo Mejía (PT) holds up printed photos of Jorge Miguel Barajas Hernández, alias “El Hummer,” and another alleged figure while accusing rivals of ties to compromised security officials. Opponent from Morena looks on at the adjacent podium.

And now, in 2025, they are names in U.S. custody files. Villarreal may believe she was singled out because of her pregnancy. The policy context makes her claim possible. But the paper trail that has followed her husband for more than a decade makes another explanation unavoidable. Despite sworn testimony, arrest warrants, public denunciations, and years of press reporting, he rose to command regional police in Coahuila. Mexican institutions allowed it. The United States did not. At Eagle Pass, the visas were pulled. No reasons were given, only the confirmation that the case was not closed. Not for him. Not anymore.

A multi-page OSINT dossier on Jorge Miguel Barajas Hernández, alias “El Hummer,” compiling his career trajectory, ties to Coahuila’s controversial GATES/Fuerza Coahuila unit, unresolved allegations in the 2012 Nuevo Laredo car-bomb case, human-rights reports, and his 2025 U.S. visa revocation. Includes a detailed timeline, press citations, and archival sources from El Mañana, Proceso, Vanguardia, and Estado Mayor.