Echoes from Alabuga: The Global Spread of Iran’s Suicide Drone Strategy

Inside Tehran’s Global Drone Strategy—From Suicide UAVs in Ukraine to Shadow Alliances in Latin America"

In the blurred lines of modern warfare, where national boundaries and military uniforms no longer define combatants, Russia’s evolving use of Iranian-supplied Shahed-136 drones has revealed not just technical advances but strategic adaptations with global consequences. Recent reporting confirms what open-source intelligence and Ukrainian field observations have long suspected: Russia is mass producing and upgrading these once-crude loitering munitions into a deadlier, harder-to-intercept fleet. With claims of Shahed-136 "2.0" enhancements now substantiated by investigative footage and firsthand testimony, the question isn’t just how these drones are changing—but where else similar tactics may soon take hold.

An Unlikely Transformation

The Shahed-136 was once dismissed by many analysts as a blunt instrument: slow, noisy, and relatively easy to jam or destroy. But reports from Ukrainian forces and military journalists tell a different story today. According to a BFBS Forces News segment aired in July 2025, Russia has introduced critical enhancements to the Shahed-136 airframe and its onboard electronics. These include hardened satellite antennas with 16-channel redundancy to resist jamming, secondary navigation systems capable of using mobile networks for guidance even when primary GPS is blocked, and upgrades allowing higher-altitude flight—doubling from a previous ceiling of around 1,000 meters to over 2,000 meters.

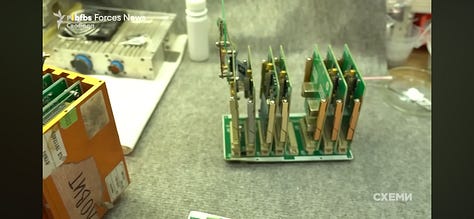

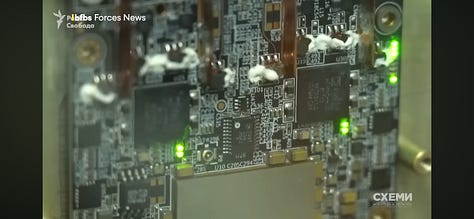

Investigative journalist Valeriya Yegoshina, based in Kyiv, cited the existence of at least two production facilities inside Russia, one in the Alabuga Special Economic Zone and another in Ingushetia. Between the two, Russian forces have reportedly produced more than 36,000 drones to date. The credibility of these upgrades is no longer speculative. Imagery shared in verified OSINT communities and cross-referenced by The Zero Lux reveals modified circuit boards, improved GNSS modules, and hardened components not present in earlier Iranian-exported Shahed units. One teardown revealed distinct modifications consistent with Russian engineering, suggesting local adaptation rather than mere assembly.

Documented Use of Shahed-136 in Urban Targets

In October 2022, a swarm of Shahed-136 drones struck Kyiv’s Shevchenkivskyi district, causing significant damage to civilian infrastructure and highlighting the threat these drones posed even before their latest upgrades, according to reports by the BBC and Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense. Additional attacks on Odessa in July 2023 followed similar patterns, using the drone’s speed and low-visibility flight path to breach urban defenses. These instances reinforce the evolution of Shahed strikes from battlefield harassment to strategic infrastructure targeting.

Engineering the Assembly Line

New findings suggest these innovations are tied directly to Russia’s use of student labor and technical apprenticeships at the Alabuga Polytechnic Institute. Russian-language investigative reports published by Protokol and other independent outlets confirm that young engineering students—some as young as 19—have been tasked with assembling loitering munitions as part of their educational curriculum. Satellite imagery and local testimonies indicate that these programs function under the guise of workforce development while streamlining drone production inside Russia’s special economic zones.

Field-captured electronics photographed and shared with The Zero Lux in July 2025 further confirm the integration of Chinese-manufactured GNSS modules, possibly BeiDou-capable, as well as Western-labeled oscillators, capacitors, and navigation circuitry. BFBS Forces News corroborated reports that Russian operators have employed real-time tracking methods and drone-based munitions with delayed detonation fuses, allowing deeper penetration into urban areas before detonation. Reverse image analysis and comparison with previous Chinese defense equipment shows these circuit designs may trace visual lineage to PLA-supported systems such as the CH-901 or variants of the Wing Loong platform.

A Costly Shield

Ukrainian air defense has responded by deploying helicopters and Western-supplied systems such as Germany’s IRIS-T and the American Patriot, but these come with high operational costs. As the drones become cheaper to manufacture and more difficult to intercept, defending against them grows disproportionately expensive. With warheads now including delayed-action fuzes and modular designs for different targets, the Shahed-136 is no longer just a tool of disruption but one of precision and psychological impact. Notably, even when unarmed, their speed and weight can cause lethal structural damage upon impact.

Cartel Interest and the Southern Front

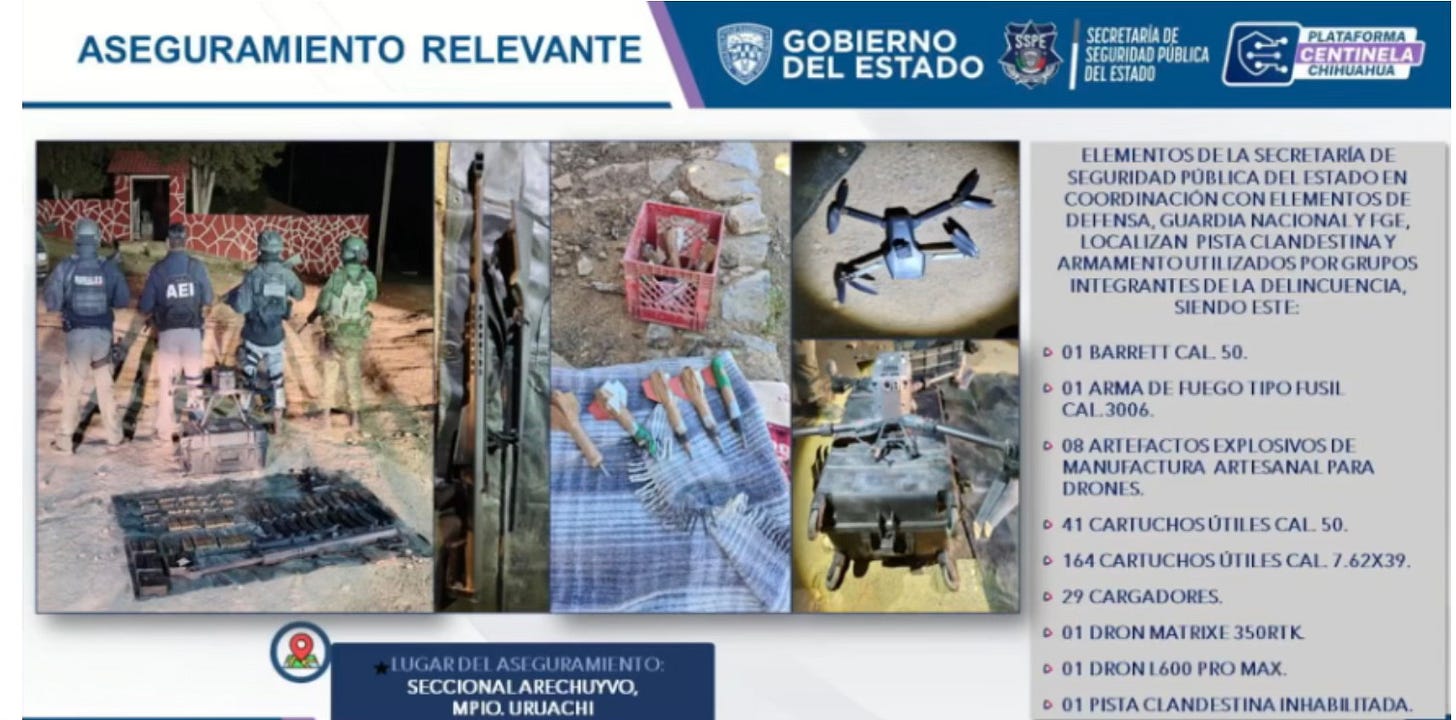

This evolution in drone warfare casts new shadows over other global regions already facing asymmetric threats—most notably Latin America. In a previous investigation published by The Zero Lux, Mexican cartel usage of commercial drones for offensive attacks was extensively documented. While no confirmed deployments of Shahed-136 or its derivatives have occurred in the Americas, Iranian state media and Western analysts have raised alarms about potential drone production expansion into Venezuela and Bolivia.

A 2024 report from Rasanah, a Saudi-based strategic studies institute, noted the presence of Iranian technical advisors and dual-use technology transfers into Latin American air defense programs. Although no conclusive proof links Shahed-style drones to Mexican cartel operations, the technological threshold for adoption is narrowing. The news outlet CiberCuba reported that Iranian drone specialists were observed in Venezuela, allegedly aiding in the assembly of loitering munitions similar in structure to the Shahed series. Meanwhile, Bolivia has expressed open interest in acquiring Iranian UAVs for “defensive purposes,” according to a 2023 CNBC report.

NewsNation investigative reporting from June 2025 included interviews with U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials who warned that the border region has seen increased use of drones for surveillance, smuggling, and potential dry-run strikes. While most drones recovered are commercial-grade, a single modified platform resembling a Shahed-like loitering design has reportedly been captured by Mexican authorities, though confirmation of its origin remains classified.

“We’re seeing cartel groups conduct dry runs with drones, flying them near border patrol stations—sometimes at night, sometimes in patterns that suggest future payload delivery,” said Jorge Ventura, a correspondent with NewsNation.

Recent open-source intelligence and European Parliament analysis describe Iran’s strategy of establishing a drone production corridor in Venezuela that mirrors the industrial path taken by Russia’s Alabuga facility. The Alabuga model—corporatized polytechnic campuses funneling labor into a drone factory staffed by teenagers and foreign recruits—offers a playbook for expansion. Local Venezuelan analyst Roberto Lafforgue states that Maduro’s government has established a drone manufacturing facility staffed with Iranian technical personnel.

Historical context further strengthens these claims. Satellite imagery dating back to 2009–2012 shows Venezuela’s CAVIM facility assembling Mohajer-2 drones from Iranian knock‑down kits, establishing a precedent for long-term military drone cooperation. A 2025 European Parliament report outlines additional Iranian military collaborations, including dual-use infrastructure projects and the repurposing of oil-for-gold barter trade routes to evade sanctions. These accounts corroborate the view that Venezuela is not merely an ideological ally of Iran—but a logistical partner in asymmetric weapons proliferation.

Hezbollah’s Shadow Network in the Americas

While much of the global focus has remained on drone components and kinetic deployments, a less visible but equally potent network has taken root. Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Lebanese militant group, has long operated financial and logistics hubs throughout Latin America. From the Tri-Border Area (TBA) where Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil meet, to more recent activities reported in Venezuela and Colombia, Hezbollah-linked networks have facilitated everything from money laundering and arms shipments to narco-financing.

The U.S. Treasury and DEA have designated several Latin American entities as Hezbollah proxies in connection with illicit financing schemes. Analysts from the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and past congressional testimony confirm that Hezbollah has acted as a logistical arm for Iranian interests in the region, a role that could feasibly extend into drone smuggling or technology transfer, especially given the group's operational experience with UAVs in Lebanon and Syria.

Dual-Use Threats and Narco-Tech

Iran’s state-aligned media amplified these developments as proof of the Islamic Republic’s “south-south cooperation,” though most Western defense analysts view this as a calculated extension of asymmetric deterrence. What makes this expansion particularly concerning is not just the hardware, but the fusion of commercial and military technologies. As our earlier report outlined, Mexican cartels already use DJI Matrice drones equipped with thermal imaging and RTK modules for night operations and target tracking. In theory, similar or greater levels of lethality could be achieved by modifying civilian airframes with improvised explosive payloads, an approach favored by both non-state actors in the Middle East and Russian-affiliated paramilitary units.

It’s important to draw a line between what has been proven and what remains within the realm of threat forecasting. There is, as of publication, no evidence that Shahed-136 drones—either Iranian or Russian-manufactured—have been exported to or deployed in the Western Hemisphere. However, there is ample open-source evidence that key technologies used in their production—including GNSS modules, antennas, and power regulators—continue to be manufactured using Western or Chinese components, sometimes re-exported through shell companies or “dual-use” civilian trade channels.

Manufactured Silence

U.S. and EU sanctions have slowed but not stopped these flows. Investigations by The Iran Primer, IPHR, and CNN confirmed that as much as 82 percent of components in some recovered Shahed drones originated from companies in the U.S., EU, and East Asia. The transition from lo-fi suicide drone to refined battlefield tool illustrates the iterative nature of modern proxy warfare. Iran has, by design or necessity, pioneered a drone doctrine that prizes scalability, deniability, and psychological attrition. Russia has taken that blueprint and optimized it for industrialized conflict.

The next iteration may not come from a battlefield in Ukraine, but from a jungle lab in South America or a narco-state safehouse in Michoacán. If the Shahed-136 was once dismissed as a noisy gimmick, today it’s a blueprint—and the longer the world underestimates it, the louder its next detonation may be.