Blueprints for Asymmetric Warfare

How China Is Exporting Drone Clones, Behavioral Surveillance, and Propaganda to Undermine the West

The next war may not begin with an invasion. It may begin with a copied drone, a falsified customs form, or a multiplayer video game.

Each of these systems—unremarkable on their own—carries strategic weight when embedded in infrastructure designed to manipulate, observe, or dominate. Together, they signal a shift in how authoritarian states like China export influence. This isn’t about espionage in the shadows. It’s about open replication, disguised logistics, and weaponized entertainment operating under the legal radar.

At The Zero Lux, we don’t chase stories. We validate them. We connect the patents, the ship manifests, the academic papers, and the public posts—often in languages our competitors don’t monitor. Because when conflict is asymmetric, reporting must be precise.

The Black Bee and the Patented Blueprint

In 2024, NORINCO—China’s state-owned defense conglomerate—unveiled a coaxial rotor drone dubbed the Black Bee. The design bears a striking resemblance to patented coaxial UAVs developed by Ascent AeroSystems, a U.S. firm now owned by Robinson Helicopter Company.

There is no record of any joint venture, licensing deal, or technology transfer between Ascent and NORINCO. But the Black Bee’s silhouette, rotor configuration, and centerline architecture align so closely with Ascent’s proprietary platform that accusations of IP theft followed swiftly.

“Looks like the China North Industries Group Corporation has taken a liking to Ascent AeroSystems’ coaxial design,” said David Smith, President of Robinson Helicopter.

The replication goes beyond aesthetics; internal structure, flight dynamics, and even dimensions appear reverse-engineered to mimic the original—without compensation or consent.

“No license. No permission. Just copy it and start making your own. Maybe the PLA will be a customer. Nice.”

The drone has since appeared in PLA-adjacent defense demonstrations, showcasing its tactical role under China’s civil-military fusion strategy. That strategy blurs the line between commercial innovation and military adoption, creating an exportable product indistinguishable from one developed under a U.S. patent.

Illicit Engines and Refrigerated Lies

Reports from open-source intelligence investigators and Indian outlet Mint reveal that Chinese drone engines have reached Russia via falsified customs forms listing the goods as “industrial refrigeration units.” These shipments, which evade U.S. and EU sanctions, include powertrains and propulsion units compatible with Iranian-designed Shahed UAVs now mass-produced in Russia’s Alabuga facility.

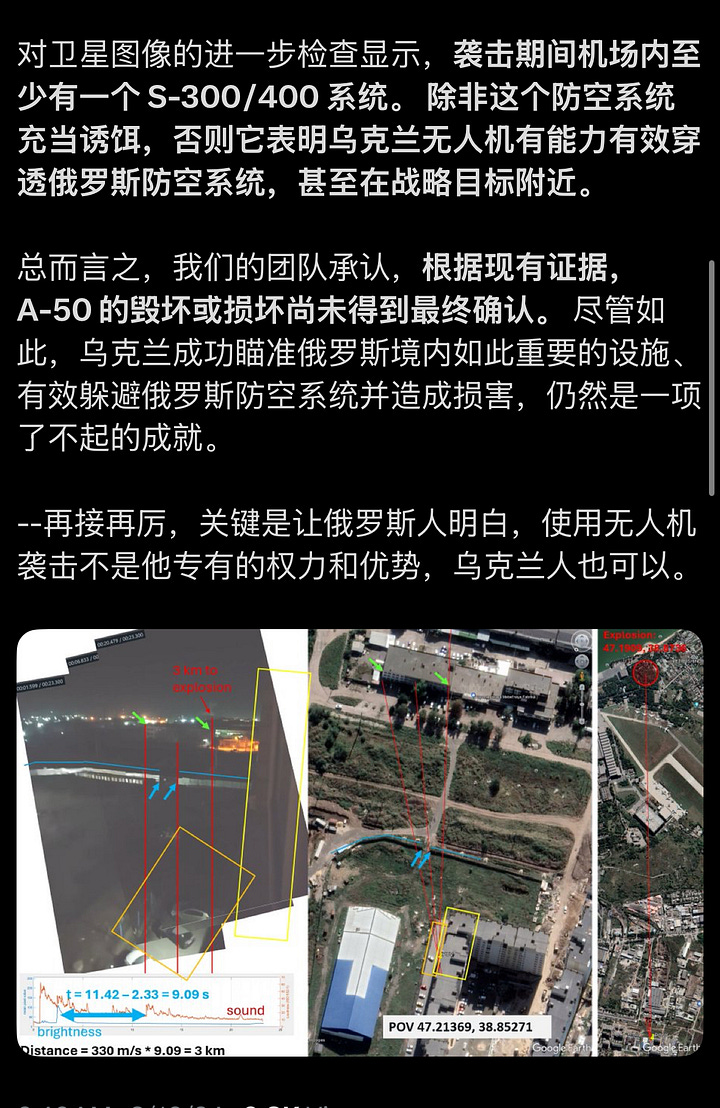

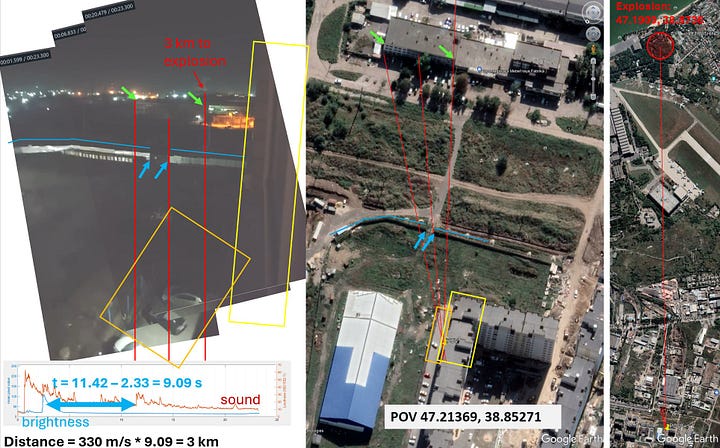

OSINT analysts have corroborated the delivery routes and impact zones using geolocated video footage, acoustic delay analysis, and satellite imagery to pinpoint the supply chain’s effectiveness and its real-time battlefield consequences. One such analysis placed the moment of explosion exactly 3 kilometers from a confirmed point-of-view, cross-verified with Google Earth coordinates and synchronized sound-brightness curves—effectively tracing the strike back to suspected imported components.

The U.K.-based open-source group Conflict Armament Research and Ukrainian military intelligence have corroborated these findings, identifying Chinese engines recovered from Russian drones launched into Ukraine. While China denies military exports to Russia, the customs trail—and visible manufacturing marks—tell another story.

Behavioral Warfare: NetEase, EOMM, and the Subtle Science of Influence

While kinetic warfare plays out over battlefields, China is also exporting a form of psychological infrastructure: data-driven behavioral modeling built into entertainment platforms.

NetEase, one of China’s largest tech firms, is the publisher of Marvel Rivals, a multiplayer shooter currently in closed testing across the West. Beneath its colorful animation and fast-paced gameplay lies a sophisticated framework—Engagement Optimized Matchmaking (EOMM)—a system designed to manipulate emotional and psychological patterns of users in real time.

NetEase researchers published their EOMM methodology in a 2017 IEEE paper, describing a matchmaking algorithm that uses telemetry data, historical performance, and predicted frustration thresholds to deliberately orchestrate winning and losing streaks—maximizing time played and emotional investment.

While EOMM is framed as a commercial tool, it produces massive volumes of Western behavioral data, legally accessible to Chinese intelligence agencies under China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law. That law requires all Chinese companies to “support, assist, and cooperate with state intelligence work.” The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s 2024 Homeland Threat Assessment warns explicitly of “nation-state efforts to malignly influence U.S. audiences” via digital platforms. [DHS, 2024 Homeland Threat Assessment]

A 2023 Center for a New American Security (CNAS) commentary further raised concerns that Chinese state-tied games may serve as intelligence platforms, warning that behavioral data harvested through gamified systems could support AI training, target profiling, or influence modeling. These fears were echoed by Israeli cybersecurity analysts cited in a Times of Israel report, which argued that such systems threaten fairness, national security, and user autonomy.

In parallel, Chinese regulators have imposed strict domestic limits on gameplay for children—including curfews, anti-addiction warnings, and spending caps—directly targeting the psychological effects of these systems on their own population. In 2021, both Tencent and NetEase were summoned by Beijing authorities to “overhaul” their gaming platforms. They were instructed to curb in-game purchases, tone down addictive mechanics, and reduce perceived “worship of money and effeminacy.” [Forbes, 2021; Global Times, 2021]

But those restrictions don’t apply to exported platforms. Systems like EOMM, stripped of domestic oversight, continue to operate in Western markets—modeling, testing, and harvesting behavioral insights from foreign users with far fewer limitations. The contradiction is stark: Chinese children are shielded from psychological overexposure, while Western users are subjected to highly adaptive, emotionally manipulative mechanics designed to maximize engagement.

The Propaganda Feedback Loop

NetEase also operates one of China’s largest media portals, curating content across its network and social platforms. In May 2024, The Zero Lux confirmed that NetEase’s verified news account on Chinese social media reposted a video originally shared by Russia’s Sputnik network. The video showcased Russian drone operations, accompanied by the translated caption: “Victory will be ours! Russia will definitely win!”—a direct amplification of wartime propaganda aimed at Chinese audiences.

In a now-archived post from May 2024, NetEase’s verified news channel amplified a Sputnik report about a Chinese drone company establishing manufacturing lines in southern Russia. The post featured an image of a large agricultural-style drone and was captioned: “Victory will be ours! Russia will definitely win!” One Chinese user, reacting critically, wrote: “Russia drags the CCP down while pretending to be close allies… when the war turns, they’ll throw China under the bus.” This layered response—NetEase amplifying Russian propaganda while users openly question the alliance—highlights how Chinese media firms can simultaneously serve as propaganda relays and domestic narrative battlegrounds.

This post was preserved, translated from Simplified Chinese, and cross-referenced with open-source video analysis to confirm the footage matched publicly available broadcasts from Russia. While NetEase markets itself as an entertainment brand in the West, its domestic media posture aligns more closely with state messaging. The company maintains a dual identity—video game publisher abroad, national amplifier at home.

Pattern Recognition as a Weapon

What makes this convergence so dangerous is that it isn’t centralized in a single program or department. Instead, it’s distributed across overlapping civilian and military layers:

Drones that mirror patented U.S. platforms, manufactured without license. Propulsion systems disguised as commercial refrigeration equipment, slipping through embargoes. Video games that learn, adapt, and track players’ emotional fragility. News platforms that publish Russian war messaging under a Chinese tech firm’s banner.

Together, these systems produce a coherent architecture of non-kinetic advantage: drones that shouldn’t exist, powered by parts that shouldn’t be there, coordinated through insights that shouldn’t be known.

The battlefield is expanding—and so is the toolkit.

Conclusion: The War That Isn’t Declared

No shots were fired to start this. But tools were deployed.

A drone design patented in the U.S. now flies under a Chinese flag. An engine disguised as a freezer powers a munition in Ukraine. A gaming algorithm rewards and punishes Western users based on emotional fragility. A tech company curates narratives for both consumers and regimes.

None of it breaks the law. But all of it breaks the paradigm.

What you see here isn’t conspiracy. It’s infrastructure: China supplies the hardware, surveils the players, and amplifies the narrative. In doing so, it builds a multi-domain system tailored for influence, disruption, and coercion—all without overt espionage.Because when conflict is asymmetric, reporting must be precise.